Adel-Naim Reyhani, Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Bologna

This article presents a framework for analyzing externalization arrangements informed by insights from studying the rightlessness of refugees. It reflects on the parameters, conceptual underpinnings, and methodological implications of categorizing externalization arrangements according to the extent to which they de facto and de jure restrict or extend access to asylum. Overall, it thereby highlights the severe effects of externalization efforts and their relationship with foundational deficiencies in the international legal order, as well as the need for profound reform.

Relying on the Law

International refugee law scholarship has generated a notable body of knowledge on the dynamics and intricacies in the interaction between the law and States’ efforts to deter refugees from territorial asylum or keep them in spaces without adequate protection. In recent years, engagement with such non-entrée policies has particularly focused on externalization arrangements.

Legal scholars have elaborated on and worked with different overlapping classifications to differentiate such measures and assess their legality. Based on a descriptive approach towards the function of state policies, e.g., scholarship subsumes relevant externalization practices under two general strands: the externalization of border control and that of asylum systems or the processing of protection claims.[1] A further perspective focuses broadly on the relationship between the actors or States involved. Here, scholars differentiate (externalized) non-entrée policies by their ‘degree of involvement by, or collaboration with, the sponsoring states’ – from diplomatic relations to direct financial incentives, support with equipment and training, the deployment of immigration officers, shared enforcement, direct control, and the tasking of International Organizations (IOs).[2] Others have identified the stages of unilateral non-admission, cooperative non-arrival, delegated non-arrival, and outsourced non-departure.[3] Moreover, the degree of formalization of such interaction has been suggested as a significant differentiating factor.[4]

Against the backdrop of the fact that ‘states retain considerable discretion to construct sophisticated interception and non-arrival policies’[5] and that the law and its enforcement mechanisms are, at least in practice, not always effective,[6] scholars have built on these diverse approaches to assess the pertinence and value of strategies, instruments, and interpretive approaches to close the accountability gap.[7] As regards push- and pull-back operations, for example, scholarship has engaged with progressive interpretations of the concepts of jurisdiction or applicability and the prohibition of collective expulsion or the principle of non-refoulment.[8] The specific mode of pull-back operations has triggered engagement with the scope of the right to leave.[9] Regarding detention, legal challenges have typically focused on rights to liberty and security.[10] States’ attempts to extraterritorially outsource their protection obligations[11] – including ‘offshore processing’ or ‘extraterritorial processing’ and specific arrangements of applying the concept of a safe third country –[12] have, e.g., triggered arguments that utilize the concept of ‘safety’.[13] In all of this, in recent years, attention has been reaching beyond international refugee law or human rights law,[14] and it is beginning to cover domestic frameworks increasingly also.[15]

This approach towards externalization typically assumes that, if incrementally advanced, the law will principally be poised to challenge increasingly sophisticated deterrence or containment policies.[16] Attempts to rationalize such optimism have included the claim that states are ‘faced with a trade-off between the efficiency of non-entrée mechanisms and the ability to avoid responsibility under international refugee law’, and that, as ‘the preference for more rather than less control persists, […] legal challenges are likely to prove successful.’[17] However, the relationship between the law and States’ migration control efforts has also been described as a ‘cat and mouse game’, thus to some extent implying the futility of legal interventions.[18]

Research built on a principle belief in the power of the law vis-à-vis deterrence or containment has critically contributed to the ‘dual imperative to simultaneously advance knowledge and protection’.[19] However, reliance on the legal framework’s capacity to effectively resolve the refugee predicament can entail the risk of veiling the view on how persisting foundational deficiencies in the international legal regime contribute to systemically excluding refugees. Revealing such circumstances requires developing and applying a more elaborate theoretical perspective for conceiving the interaction between externalization and international refugee law. For this purpose, the concept of ‘rightlessness’ is a pertinent basis for a perspective complementary to identifying violations of the law.[20]

The Prism of Rightlessness

The term ‘rightlessness’ appears in the political theory of Hannah Arendt and her elaborations on the ‘right to have rights’.[21] With it, she refers to the dilemma created by the nation-state-based legal order when individuals are fundamentally cast out from the pale of the law.[22] In this sense, rightlessness connects to the original anomalous position of refugees who, because they have lost the protection as nationals of their country of origin,[23] face exclusion from a system that views nationality as ‘the principle link’ between individuals and the protection of the law.[24] The rightlessness of refugees thus does not denote the loss of specific rights. Instead, in such condition, refugees lack a rightful ‘place in the world’ – they are indeed ‘expelled from humanity’.[25]

Research demonstrates how, despite significant developments in international law, including the 1951 Convention and the complementary system of international human rights law, current policies expose refugees to a condition of rightlessness that persists due to foundational deficiencies in the structure of the legal order.[26]

Itamar Mann, e.g., has shown that a ‘policy fully compliant with international law can tolerate large-scale migrant deaths at sea.’[27] He reveals how violence and death in the Mediterranean Sea that occur beyond the jurisdiction of any state can be understood as maritime legal black holes generated by the law itself. His exploration builds on the observation that ‘these deaths … stem from the way sovereignty and human rights mutually construct jurisdiction, posit jurisdictional limitations and delineate areas where no such jurisdiction exists.’ In this context, he crucially introduces the notion of ‘de jure’ as differentiated from ‘de facto’ rightlessness’, thereby describing the condition of ‘people […] whose deaths are the direct result of human decisions but are not, legally, a violation of their rights (as a matter of lex lata).’[28] He thus suggests pursuing ‘a specific mode of analysis in international law’ that engages with the structure of the law.

Ayten Gündoğdu has demonstrated how, at the ‘borders of human rights’, refugees can be exposed to contemporary rightlessness. In analyzing the Hirsi decision of the ECtHR,[29] amongst others, she claims that the Court – through reinforcing the aspect of territoriality as the norm and extraterritoriality as the exception – casts refugees and other migrants in a legal position that establishes a dependency on the favors and discretions of authorities.[30]

A further example of persisting rightlessness has been identified in the condition of refugees detained by local armed groups in ungoverned areas in Libya. For them, rights facilitating their movement toward asylum remain theoretically unavailable. Such rightlessness in a dysfunctional state relates to ‘a state-bound conception of international refugee law that connects the disintegration of the law to the disintegration of the state’.[31] It finds expression in a model of territorially defined human rights jurisdiction ‘that is dependent on the capacity of states to exert authority’.[32] Rightlessness in ungoverned areas thus constitutes a troubling spatial anomaly in international law that is superimposed on the original personal anomaly of the refugee condition that the 1951 Convention seeks to resolve.

The perspective of rightlessness outlined here agrees with the general literature on containment and deterrence that the law can give States room for manoeuvre to avoid responsibility. However, it does not agree that an incremental advancement of the law could sufficiently address the refugee dilemma. Instead, it also establishes a connection to the foundational structure of the law and its deficiencies. It hence claims that strategies of closing the accountability gap or ‘catching the mouse’ within the available legal architecture cannot alone address the predicament of refugees – i.e., that there is a need for more profound or more radical interventions or reform.[33]

An Analytical Framework

This article argues that the concept of rightlessness can inform a more comprehensive and nuanced refugee law perspective on externalization. The following elaboration articulates the central parameters and conceptual underpinnings of such an analytical framework.

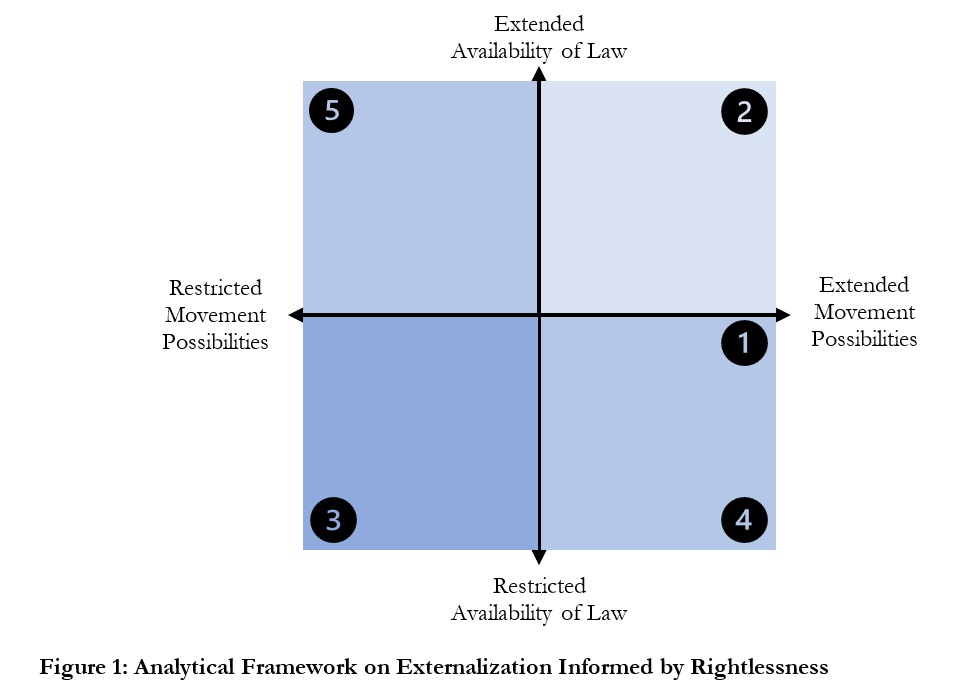

At the heart of the insights gained from studying rightlessness lies the distinction between the de jure and de facto exclusion of refugees. De jure rightlessness thereby denotes when refugees (whose anomalous legal status has not yet been resolved) face the theoretical unavailability of the rights that would facilitate and secure their movement toward asylum. De facto rightlessness, in turn, describes conditions in which such rights, even if theoretically available, are violated or not implemented in practice, and, consequently, movement is prevented or obstructed. To capture the reality of the position of refugees affected by deterrence or containment more adequately, however, de jure and de facto rightlessness can be conceptualized as continuums represented by vertical and horizontal trajectories. On the horizontal trajectory, de facto rightlessness can, e.g., be absolute – when there is a complete lack of practical access to a potential country of asylum – or relative – when movement towards asylum remains within reach. On the vertical trajectory, in turn, the position of refugees is defined by the extent to which their rights that facilitate access to asylum have theoretically emerged, thus including, at its bottom end, the potential abyss of a legal black hole.[34]

In the main thread of scholarly engagement, the term externalization is predominantly used in the context of deterrence or containment. While such will likely remain the most relevant research setting, it is necessary to acknowledge that externalization can also strengthen (access to) protection. Indeed, a framework intending to understand the creation of rightlessness should also register and specify instances when externalization contributes to its resolution. For this purpose, both trajectories can be conceived of as bidirectional.[35]

The figure below visualizes the suggested analytical framework on externalization informed by insights from studying rightlessness.

The center-point of the figure represents the original position of refugees who require surrogate protection elsewhere to remedy their anomalous status in international law. This position, however, is always contextualized and subject to specific circumstances that exist prior to or independent of the externalization intervention. Externalization arrangements influence this context-specific position by restricting or extending 1. refugees’ possibilities for physical movement towards such protection (the horizontal trajectory) and 2. the availability of relevant law (the vertical trajectory). In other words, the positioning of arrangements in this framework is defined by the context-specific effects of measures. Thus, an arrangement of similar substance and character would require an adapted allocation based on differences in circumstance.

Accordingly, traditional resettlement schemes for refugees in unsafe transit countries (1),[36] e.g., would be positioned in the center-right of this figure. When connected to a strong right to such resettlement, (2) such measure would move to the top right. Containing refugees in ungoverned territories of dysfunctional states (3) would fall to the bottom-left corner. A quota-based discretionary evacuation scheme in such a context would be allocated to the bottom right corner (4). On the top left, one could, e.g., place a strict detention policy in transit zones connected to removals, which, however, includes an advanced and robust judicial review (5).

These overly generalized examples intend to clarify the conceptual underpinnings of the suggested framework. A more precise allocation of concrete externalization arrangements would naturally demand an in-depth engagement with their functioning and impact in specific contexts. Moreover, it is also necessary to stress that the positioning of specific measures depends on interpreting the rights of refugees, which are often contested and fragmented. Finally, applying this framework to an increasing number of externalization contexts will contribute to its further refinement.

Methodological Implications

The suggested analytical framework raises specific methodological questions related to the (doctrinal) analysis of international refugee law. The elaboration below contains reflections on relevant intricacies and suggestions that seek to assist in its application.

The analytical framework – and arguably studying rightlessness in general – is guided by an aim ‘internal’[37] to international refugee law: the imperative to protect refugees from being cast out from the pale of international law by resolving their anomalous legal status. In its analysis of the law as it is, then, it follows that such research is normative: It evaluates the law against the standard of its intended underlying objective. Thus, it can serve as a basis for a conversation on necessary legal reforms but cannot, in itself, result in concrete suggestions to that end.

The critical value of an analytical lens informed by the concept of rightlessness is its ability to connect to underlying deficiencies in the foundational structure of international refugee law. ‘Foundational structure’ here refers to the premises and basic principles governing the emergence, distribution, and interaction of obligations, rights, and responsibilities of relevance for the asylum access of refugees.[38] It thus includes, amongst others, work on the interconnection between (the animating purpose of) international refugee law and the sovereign territorial state-based international order, the interaction between the 1951 Convention and other regimes, such as international human rights law, or the notion of jurisdiction as a relationship of authority between states and potential right-holders.[39] ‘Deficiencies’ are those aspects of this structure that are dysfunctional or detrimental concerning the purpose of resolving rightlessness.

It follows that interpreting international refugee law in the context of externalization and from a perspective of rightlessness focuses on identifying the limitations of the law in relation to accessing asylum. In doing so, however, it should uphold that the interpretation of treaty obligations in refugee protection should seek to advance their effectiveness,[40] yet without ‘pretending that rules exist where there are none’.[41]

Thus, applying the suggested analytical framework does not imply a limited perspective of what the relevant law is or can be. Instead, it applies an integrated approach to conceiving international refugee law, its sources, and interpretation, thus building on the insight that a holistic understanding ‘opens up new perspectives to rethink and revisit the reach of refugee protection.’[42] The 1951 Convention naturally plays a crucial role in such research despite its inapplicability in some territories, given that it has been designed specifically to resolve rightlessness by providing surrogate protection. However, while emphasizing the relevance of a response specifically from refugee law in the narrower sense, a comprehensive study of rightlessness requires integrating all law that significantly regulates access to asylum, including from general international law and different specialized frameworks. Moreover, it is necessary to include the obligations and responsibilities of all states involved or cooperating in the externalization efforts, including to avoid the risk of a bias towards ‘interpretations of international law originating in the global North.’[43] Finally, it should also cover how the potential responsibility or liability of NSAs, including IOs and private actors, could impact rightlessness and its resolution.[44]

Beyond the substance of relevant rights that regulate asylum access, understanding the creation of rightlessness demands engagement with the (sources of the) interrelating concepts of applicability, attributability, and accountability.

The notion of applicability is a key determinant for the availability of rules that can facilitate access to asylum for refugees subjected to restrictive externalization. The degrees of the inapplicability of a framework thus create different expressions of rightlessness along the vertical trajectory. Research informed by rightlessness thus should engage in an in-depth exploration of distinct conceptions of applicability rules found in different frameworks, such as international human rights law – with its emphasis on the notion of (territorial and extraterritorial) jurisdiction –[45] the 1951 Convention,[46] and other instruments such as the EUFRC.[47]

The notion of attributability is crucial for studying rightlessness on both trajectories. The law of state responsibility and the rules on the responsibilities of IOs principally function as a secondary system.[48] Therefore, attributability questions follow once applicability (as a threshold criterion) is established. However, there exists both substantial overlap and interdependence between applicability and attributability. Moreover, the two concepts can apply independently, such as in the case of derived responsibility.[49] Thus, even without applicability, the theoretical emergence of rights can be facilitated via attribution.

The inclusion of the concept of accountability in the analytical framework is less straightforward. While accountability naturally relates to the legal position of refugees, respective mechanisms essentially aim to contribute to the practical enforcement of rights and are conceptually unrelated to their theoretical availability. It is thus suggested that the strength of accountability systems be considered primarily as a factor that influences the position of refugees on the horizontal trajectory – i.e., regarding facilitating or restricting movement.

Conclusion

The perspective informed by the concept of rightlessness developed here intends to provide a more comprehensive and nuanced framework for analyzing externalization arrangements. However, the primary value of this framework lies in its potential to become a prism that brings into view instances of the fundamental legal exclusion of refugees affected by externalization. This, in turn, prompts an urgent evaluation of not only policy choices but also deficiencies in the foundational structure of the international legal order, thus complementing the discussion of enforcement issues with a conversation about profoundly advancing the law in alignment with its original purpose.

Acknowledgement

This article was funded by the ERC-2022-STG Gatekeepers to International Refugee Law? – The Role of Courts in Shaping Access to Asylum (ACCESS), Grant No. 101078683

Footnotes

[1] Cantor et al., ‘Externalisation, Access to Territorial Asylum, and International Law’ International Journal of Refugee Law (2022).

[2] Gammeltoft-Hansen and Hathaway, ‘Non-Refoulement in a World of Cooperative Deterrence’, 53 Columbia Journal of Transnational Law (2014) 235.

[3] Lavenex, ‘The Cat and Mouse Game of Refugee Externalisation Policies: between law and politics’, in A. Dastyari, A. Nethery and A. Hirsch (eds), Refugee Externalisation Policies: Responsibility, legitimacy and accountability (2023), 27.

[4] Nicolosi, ‘Externalisation of Migration Controls: A Taxonomy of Practices and Their Implications in International and European Law’ Netherlands International Law Review (2024) 1.

[5] G. S. Goodwin-Gill and J. McAdam, The Refugee in International Law (2021), at 416.

[6] Costello and Mann, ‘Border Justice: Migration and Accountability for Human Rights Violations’, 21 German Law Journal (2020) 311; Freier, Karageorgiou and Ogg, ‘Challenging the Legality of Externalisation in Oceania, Europe and South America: an impossible task?’ Forced Migration Review (2021).

[7] Among many, see, e.g., Moreno-Lax, ‘The Architecture of Functional Jurisdiction: Unpacking Contactless Control-On Public Powers, S.S. and Others v. Italy, and the “Operational Model”’, 21 German Law Journal (2020) 385; Boer, ‘Closing Legal Black Holes: The Role of Extraterritorial Jurisdiction in Refugee Rights Protection’, 28 Journal of Refugee Studies (2014) 118.

[8] N. Markard, ‘A Hole of Unclear Dimensions: Reading ND and NT v. Spain’; C. Hruschka, ‘Hot Returns Remain Contrary to the ECHR: ND & NT before the ECHR’ (2020).

[9] Markard, ‘The Right to Leave by Sea: Legal Limits on EU Migration Control by Third Countries’, 27 European Journal of International Law (2016) 591; McDonnell, ‘Challenging Externalisation Through the Lens of the Human Right to Leave’, 71 Netherlands International Law Review (2024) 119.

[10] M. Akkerman, ‘Outsourcing Oppression: How Europe externalises migrant detention beyond its shores’ (2021); I. Majcher, M. Flynn and M. Grange, Immigration Detention in the European Union (2020), at 451.

[11] G. Noll, J. Fagerlund and F. Liebaut, ‘Study on the Feasibility of Processing Asylum Claims Outside the EU Against the Background of the Common European Asylum System and the Goal of a Common Asylum Procedure’ (2002); Cantor et al., supra note 1, or already Helton, ‘Refugee Determination under the Comprehensive Plan of Action: Overview and Assessment’, 5 International Journal of Refugee Law (1993) 544.

[12] Lambert, ‘Extraterritorial Asylum Processing: the Libya-Niger Emergency Transit Mechanism’ (2021); Mainwaring, ‘Beyond Europe’s Borders: containment and deterrence across the Mediterranean Sea’, in A. Dastyari, A. Nethery and A. Hirsch (eds), Refugee Externalisation Policies: Responsibility, legitimacy and accountability (2023), 124; Loughnan, ‘Active Neglect and the Externalisation of Responsibility for Refugee Protection’, in A. Dastyari, A. Nethery and A. Hirsch (eds), Refugee Externalisation Policies: Responsibility, legitimacy and accountability (2023), 105; Ellis, Atak and Abu Alrob, ‘Expanding Canada’s Borders’ Forced Migration Review (2021).

[13] Freier, Karageorgiou and Ogg, ‘The Evolution of Safe Third Country Law and Practice’, in C. Cathryn, F. Michelle and M. Jane (eds), The Oxford Handbook of International Refugee Law (2021); Giuffré, Denaro and Raach, ‘On ‘Safety’ and EU Externalization of Borders: Questioning the Role of Tunisia as a “Safe Country of Origin” and a “Safe Third Country”’, 24 European Journal of Migration and Law (2022) 570.

[14] Costello and Mann, supra note 6.

[15] Tan and Gammeltoft-Hansen, ‘A Topographical Approach to Accountability for Human Rights Violations in Migration Control’, 21 German Law Journal (2020) 335, at 337.; Pijnenburg, ‘Externalisation of Migration Control: Impunity or Accountability for Human Rights Violations?’, 71 Netherlands International Law Review (2024) 59 and Costello, Foster and McAdam, ‘Introducing International Refugee Law as a Scholarly Field’, in C. Cathryn, F. Michelle and M. Jane (eds), The Oxford Handbook of International Refugee Law (2021), 1 at 18.

[16] Freier, Karageorgiou and Ogg, Challenging the Legality of Externalisation in Oceania, Europe and South America, supra note 6.

[17] Gammeltoft-Hansen and Hathaway, supra note 2, at 284. Gammeltoft-Hansen and Tan, ‘The End of the Deterrence Paradigm?: Future Directions for Global Refugee Policy’, 5 Journal on Migration and Human Security (2017) 28, at 46.

[18] Lavenex, supra note 3.

[19] Byrne and Gammeltoft-Hansen, ‘International Refugee Law between Scholarship and Practice’ International Journal of Refugee Law (2020).

[20] Mann, ‘Maritime Legal Black Holes: Migration and Rightlessness in International Law’, 29 European Journal of International Law (2018) 347, at 369.

[21] H. Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (2nd ed., 1962); E. Larking, Refugees and the Myth of Human Rights (1st ed., 2016), at 136.

[22] Arendt, supra note 21, at 297.

[23] As described by UN Ad Hoc Committee on Refugees and Stateless Persons, ‘A Study of Statelessness’ (Lake Success – New York, 1949). See also D. Schmalz, Refugees, Democracy and the Law (2020), at 54 et. seq; A. Kesby, The Right to Have Rights (2012); Gündoğdu, Rightlessness in an Age of Rights, supra note 23; Reyhani, ‘Refugees’, in C. Binder, M. Nowak, J. A. Hofbauer and P. Janig (eds), Elgar Encyclopedia of Human Rights (2022); A.-N. Reyhani, ‘The Rightlessness of Refugees in Libya’ (2021) (Dissertationat Universität Wien, Wien). But see also Tuitt, ‘Refugees, Nations, Laws and the Territorialization of Violence’, in P. Fitzpatrick and P. Tuitt (eds), Critical Beings: Law, Nation and the Global Subject (2004).

[24] R. Jennings and S. A. Watts, Oppenheim’s International Law (2008), at 857. See, e.g., also the ICJ’s Judgment of 6 April 1955 in the case of Nottebohm (Liechtenstein v. Guatemala).

[25] Arendt, supra note 21, at 296. For a reflection, see, among many, Oudejans, ‘What is Asylum?: More than protection, less than citizenship’, 27 Constellations (2020) 524; Kesby, supra note 23, at 15 et. seq; E. Haddad, The Refugee in International Society (2008), at 82 et. seq.

[26] Mann, supra note 20; Reyhani, ‘Anomaly upon Anomaly: The 1951 Convention and State Disintegration’, 33 International Journal of Refugee Law (2021) 277; Larking, supra note 21; Gündoğdu, ‘Borders of Human Rights: Territorial Sovereignty and the Precarious Personhood of Migrants’, in B. Schippers (ed.), Critical Perspectives on Human Rights (2018), 191; Mann, supra note 20; Reyhani, Anomaly upon Anomaly, supra note 26; Hirsch and Bell, ‘The Right to Have Rights as a Right to Enter: Addressing a Lacuna in the International Refugee Protection Regime’, 18 Human Rights Review (2017) 417; Stewart, ‘”A New Law on Earth”: Hannah Arendt and the Vision for a Positive Legal Framework to Guarantee the Right to Have Rights’ SSRN Electronic Journal (2021).

[27] Mann, supra note 20, at 348.

[28] Ibid., at 369.

[29] ECtHR, Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy [GC], Appl. 27765/09, 23 February 2012.

[30] Gündoğdu, ‘Borders of Human Rights’, supra note 26, at 200.

[31] Reyhani, Anomaly upon Anomaly, supra note 26.

[32] Note that the study’s underlying interpretation of the scope of jurisdiction is challenged in A. Berkes, International Human Rights Law Beyond State Territorial Control (2021).

[33] Beyond Mann, supra note 20 and Reyhani, Anomaly upon Anomaly, supra note 26 also D. Owen, What do We Owe to Refugees? (2020); T. A. Aleinikoff and L. Zamore, The Arc of Protection (2019).

[34] Reyhani, Anomaly upon Anomaly, supra note 26.

[35] In this sense, and for the sake of conceptual clarity, a differentiation between (legally or factually) restrictive and extensive externalization arrangements is indicated.

[36] Parusel, ‘Why Resettlement Quotas Cannot Replace Asylum Systems’ Forced Migration Review (2021).

[37] Taekema, ‘Theoretical and Normative Frameworks for Legal Research: Putting Theory into Practice’ Law and Method (2018).

[38] Note the difference in using the term ‘structure’ in Mann, supra note 20, at 369.

[39] Haddad, supra note 25.

[40] J. C. Hathaway, The Rights of Refugees under International Law (2021), at 128 et. seq. But see also Hailbronner, ‘Review of James C. Hathaway, The Rights of Refugees under International Law’, 18 International Journal of Refugee Law (2006) 722.

[41] Goodwin-Gill, ‘The International Protection of Refugees: What Future?’, 12 International Journal of Refugee Law (2000) 1, at 6. For a reflection, see also Byrne and Gammeltoft-Hansen, supra note 19, at 190 et. seq.

[42] Chetail, ‘Moving Towards an Integrated Approach of Refugee Law and Human Rights Law’, in C. Cathryn, F. Michelle and M. Jane (eds), The Oxford Handbook of International Refugee Law (2021), 202 at 220.

[43] M. Achour & T. Spijkerboer, The Libyan litigation about the 2017 Memorandum of Understanding between Italy and Libya (2020).

[44] A. Clapham, Human Rights Obligations of Non-state Actors (2010) and Berkes, supra note 32.

[45] Besson, ‘The Extraterritoriality of the European Convention on Human Rights: Why Human Rights Depend on Jurisdiction and What Jurisdiction Amounts to’, 25 Leiden Journal of International Law (2012) 857.

[46] Moreno-Lax and Costello, ‘The Extraterritorial Application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights: From Territoriality to Facticity, the Effectiveness Model’, in S. Peers, A. Ward, J. Kenner and T. Hervey (eds), The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights: A commentary (2014).

[47] Lenaerts, ‘Exploring the Limits of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights’, 8 European Constitutional Law Review (2012) 375, at 378.

[48] J. Crawford, State Responsibility (2013), at 64.

[49] Milanović, ‘Jurisdiction and Responsibility: Trends in the Jurisprudence of the Strasbourg Court’, in A. van Aaken and I. Motoc (eds), The European Convention on Human Rights and General International Law (2018).