Alice Mesnard (Reader, City University of London, United Kingdom), Filip Savatic (Teaching Fellow, Sciences Po, France), Jean-Noël Senne (Professor, University of Paris-Saclay, RITM, France), and Hélène Thiollet (CNRS Researcher, Sciences Po, France)

This article examines the impact of externalisation policies on migration flows, with a particular focus on the EU-Turkey Statement of March 2016. While externalisation policies are designed to prevent unauthorised migration, they often conflate different migrant categories, leading to inconsistent humanitarian protections. Using data from Frontex and Eurostat, the study reveals that likely refugees tend to follow concentrated migratory routes and are less adaptable to policy changes, whereas likely irregular migrants are more dispersed and adjust their routes in response to new policies. The findings indicate that the EU-Turkey Statement primarily deflected irregular migrants to alternative routes, but failed to stop Syrian refugees from crossing into Greece. The study highlights the need for migration policies that balance control measures with humanitarian obligations, emphasising the complexities and contradictions of externalisation efforts.

Introduction

The impact of public policies on migration flows, particularly in preventing (ill-defined) irregular migration, has generated significant scholarly and policy.[1] The effectiveness of migration policies depends upon the relative congruence between policy discourses, policies on paper, policy outputs, and, ultimately, policy implementation.[2] It also depends upon organizational and political logics within policy circles and across institutions, often leading to reinterpretations, decoupling, and contradictions within and across policies, thus creating a messy migration policy domain.[3] In a context where migration and asylum policies involve a complex mix of tools and instruments, a variety of actors and institutions with different rationales and goals, and a sometimes explicitly contradictory set of objectives, policies run the risk of being, at best, incoherent, and, at worst, failures.

Such risks seem to be particularly high with respect to the “externalization” of migration controls. Externalization refers to attempts by migrant destination states to relocate control over migration flows to countries from which migrants come or through which they travel.[4] The stated ostensible goals of externalization policies are to prevent unauthorized migration before individuals reach the borders of destination states, while respecting legal obligations towards refugees and asylum seekers. Externalization involves diplomatic cooperation and variegated forms of partnerships for migration and asylum management between migrant destination states and origin/transit states. It also reflects changing and asymmetric power relations, where origin/transit states may leverage economic or political resources and to extort destination states for funds or other policy related linkages.[5]

However, while externalization policies may aim to only reduce irregular migration, they can end up conflating unauthorized flows of forcibly displaced individuals with the “illegal” migration of individuals migrating for reasons other than fear of persecution and violence, obliterating the diversity of motivations and statuses of people on the move who cross borders “irregularly.” The notion of “mixed migration” acknowledges that migration flows involve individuals travelling with various motivations, challenging states and policy-makers to ensure humanitarian and human rights protections for all migrants while managing border crossings.[6] Although policy-makers may publicly state their support for the protection of forcibly displaced and persecuted individuals, the distinction between refugees and other migrants remains unclear in the implementation of border and externalization policies. As a result, externalization has been widely criticized for undermining liberal democratic norms, reenforcing postcolonial domination, and engendering human rights violations.[7]

Additionally, scholars have argued that policies of geographical containment have historically been implemented by countries in the Global North to keep both refugees and other migrants from the Global South away from their borders.[8] Whether practices of containment have (un)intended effects remains difficult to explore; nevertheless, historical containment strategies across geopolitical divides have been characterized by forced immobilization[9] and attempts at the “remote control” of population movements.[10] These dynamics have become prevalent during crises such as the Arab Spring and the ensuing Syrian civil war, as well as upheavals in Venezuela and Central America.[11]

In this context, our chapter interrogates the effects of externalization policies on different categories of migrants, focusing on unauthorized migration flows to Europe, drawing on our companion paper Mesnard et al.[12] Specifically, it investigates whether these policies impact unauthorized migration flows at all, and whether any impacts that are identified vary across different migrant categories. We anticipate that individuals primarily migrating due to violence and persecution (i.e. “likely refugees”) are more likely to be concentrated geographically on single primary migratory routes, while those primarily migrating for economic reasons (i.e. “likely irregular migrants”) are more likely to be dispersed across space. In turn, we argue that externalization policies will have a distinct impact on different categories of migrants, with those migrating due to violence and persecution less likely to adjust to the implementation of new policies by altering their migratory trajectories. We expect to identify these trends as we posit that refugees are relatively more likely to seek the shortest route to their desired destination, less likely to have the time and resources to consider the costs of travel following the adoption of a new policy, likely to believe that their right to asylum will not be infringed by new policies, and less likely to invest in developing networks that could lead them on alternative migratory trajectories.[13] We focus on the EU-Turkey Statement of March 2016, a paradigmatic example of externalization, to assess the effects and implications of externalization policies on unauthorized migratory flows and the degree to which our expectations are supported empirically.

Through our analyses, we show that forced and voluntary migration flows differ geographically and temporally – the former being relatively more concentrated in both time and space – while defining those categories considering asylum acceptance rates by nationality in destination states. In particular, our analyses indicate that likely refugees are concentrated on single migration routes, while likely irregular migrants are dispersed across multiple routes. Likely refugees are also less likely to shift to alternative routes following the adoption of restrictive policies, while likely irregular migrants are deflected to alternative migratory routes following policy adoption. More precisely, through an event study analysis of migration flows preceding and following the EU-Turkey Statement, we find that the policy deflected likely irregular migrants to alternative routes but did not significantly impact the number of likely refugees crossing from Turkey to Greece, as explicitly intended.

Thus, the EU-Turkey Statement exemplifies the complexities and contradictions of externalization policies. While intended to manage migration flows, externalization can deflect rather than stop “irregular” migration while simultaneously undermining humanitarian protections. Our findings therefore reveal important legal and practical inconsistencies across externalization policies, in line with existing critiques.[14] By blocking asylum seekers from seeking humanitarian protection, they violate international and national asylum laws, all while irregular migrants find alternative pathways to reach their desired destinations. In this way, the EU-Turkey Statement failed to stop Syrian refugees from crossing into Greece while primarily deflecting other migrants from Turkey to Libya. Altogether, our findings underscore the need for policies that address complex migration dynamics and uphold international legal standards. Most importantly, effective migration policy design requires balancing control measures with humanitarian obligations.

State of the Art on the Effects of Border Policies

Studies of border policies, their (un)intended effects, and (in)efficacy are extensive. However, studies specifically focused on externalization are less prevalent. Those which have been conducted typically examine either general socio-political impacts or the dynamics behind the cooperation between migration origin/transit and destination states.[15] To our knowledge, this research has not assessed whether externalization impacts the size and direction of migratory flows, or whether it may have differential impacts on categories of migrants given the time and place of policy implementation.[16]

While ostensibly maintaining a distinction between forced and irregular migrants in their objectives, externalization policies often fail to distinguish between these groups, treating all unauthorized border crossings as “illegal.” In previous work,[17] we have critically examined the role of Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, in shaping migration narratives through its data on “irregular/illegal border crossings” (IBCs).[18] We have shown that Frontex’s labelling of migrants as “irregular” or “illegal” is politically constructed and misleading. Our empirical analysis reveals that a significant proportion of those labelled as irregular migrants are likely refugees who would probably obtain asylum in 31 European destination states given asylum acceptance rates by nationality. Most notably, during the 2015 migration crisis, about 75.5% of IBCs were likely to be granted refugee status. Our work highlights the endogenous nature of political dynamics behind border policies: the more IBCs Frontex counts, the more resources it potentially receives, perpetuating the narrative of a migration crisis requiring securitized responses. This misrepresentation fuels public misconceptions and engenders support for restrictive border policies, which contradict the more liberal asylum policies and practices that European states implement domestically.

Given the mixed nature of migrations behind IBCs, externalization policies may have distinct effects on different categories of migrants. While we focus on policy impacts given migrant categories, we acknowledge that these categories are politically constructed and imposed ex post by destination states. Individuals typically migrate for a variety of reasons, all falling within a continuum of motivations related to various migration drivers.[19] Ideal-type “refugees” who leave solely due to violence and “economic migrants” who seek employment opportunities hardly reflect migration experiences on the ground.

Nevertheless, these categories are embedded in public policies across the Global North and increasingly exported to partner countries in the Global South through externalization. Therefore, we use the categories of “refugee” and “irregular migrant” in a probabilistic and pragmatic manner, defined by asylum adjudications in destination states. In particular, we argue that the immediacy and disruption caused by violence and persecution translate into adaptation capabilities.[20] We thus posit that there is a parallel continuum between migration categories and migration capabilities, with likely refugees less willing and able to alter their migration than other migrants.

Since externalization policies typically involve cooperation with one origin/transit state at a time, they do not systematically block migration across all possible routes. As a result, we anticipate that individuals less likely to obtain refugee status are more likely to deflect to alternative routes to reach their desired destinations after a public policy is adopted. In contrast, those more likely to obtain refugee status are less likely to deflect, persistently choosing the shortest route to their destination, and therefore more likely to be blocked. Thus, we explore whether the likelihood of obtaining refugee status relates to the shifting of migratory pathways following the adoption of new externalization policies.

In addition, geographical distance, along with other demographic, social, cultural, and economic factors, affect the impact of policies on migration flows. Greater distance generally decreases migration flows since it increases the financial and non-monetary costs of travel. We expect individuals traveling from countries of origin far from a migration route affected by a policy will alter trajectories to a greater extent than those close. However, we again anticipate that this is more likely for likely irregular migrants who have a relatively greater ability to adjust.

Data and Research Design

We use data from Frontex[21] on IBCs and Eurostat[22] on first instance asylum acceptances/rejections by nationality across 31 European destination states. Frontex data represent the number of times the borders of the EU or Schengen Area[23] have been crossed by persons without prior authorization monthly since January 2009 and indicate the nationality of those identified at a crossing. Data are broken down into nine migratory routes into Europe.[24]

Overall, Frontex data can be criticized for inflating the number of crossings given the potential for double-counting individuals, although this may be offset by undetected crossings. In any case, the data offer the only systematic information on the number and characteristics of unauthorized migration to Europe. Eurostat data on first instance asylum acceptances are provided annually for each of the 31 destination states and indicate the nationality of everyone who applied for asylum. We consider any form of status granted to individuals as an asylum “acceptance.”[25]

We developed a method based on Savatic et al[26] to divide data on flows into those likely to obtain asylum in destination states (“likely refugees”) and those likely not to receive international protection (“likely irregular migrants”).[27] Using Eurostat data[28], we calculate the annual weighted average asylum acceptance rate by nationality across all 31 destination states. For example, for Syrian nationals, the weighted average considers the annual acceptance rate in Germany to a greater extent than in other states given that Germany adjudicated the largest share of Syrian asylum applications. Given the weighted average, we can split the data on IBCs into our two categories.

Using our method, we conduct a multifaceted analysis of unauthorized flows to Europe and the impacts of the EU-Turkey Statement. We begin with a descriptive overview of IBCs from 2009-2020 and their division into likely refugees and likely irregular migrants. We examine the degree to which both categories of migrants are concentrated on single primary routes to Europe. We then evaluate the impact of the EU-Turkey Statement on the number of IBCs identified across major migration routes to Europe and whether that policy had differential effects on individuals estimated to be likely refugees or likely irregular migrants. Our analysis has three parts: an event study analysis to assess the impact on aggregate IBCs, an evaluation of the potential heterogeneous effect of the policy given our two migrant categories, and an evaluation of the robustness of the results by splitting the sample by proximity between countries of origin and the entry points into Europe represented by major routes.

To examine changes in aggregate migration flows following the EU-Turkey Statement, we use an event study approach, restricting our analysis to 12 months before and after March 2016. Given that many nationalities are not identified on several routes across many months, the data contain numerous zeros, so we rely on Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood (PPML) estimations. Standard errors are clustered at the origin-time level. In turn, to assess the potential differential effects of the policy on likely refugees and likely irregular migrants, we estimate the change in the number of both categories of IBCs before and after March 2016. This specification includes an interaction term between a dummy variable for the period after the policy was implemented and a dummy for asylum likelihood set at 75%.[29] We assess the robustness of our results by applying weights given the number of IBCs by nationality across routes, as well as by excluding Syrian nationals form the analysis given that they are concentrated on one primary route and represent a majority of crossings there.[30]

Results

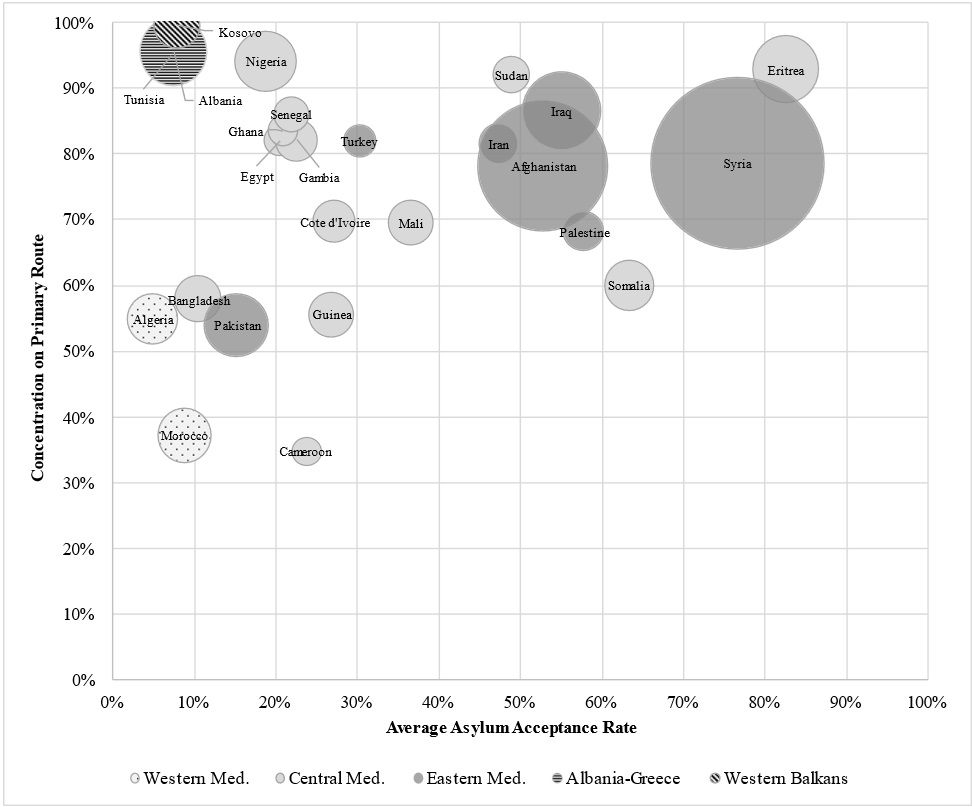

Our descriptive analysis of migration flows to Europe reveals that nationals likely to obtain refugee status are concentrated on single primary migratory routes while likely irregular migrants may or may not be concentrated. For example, Moroccan nationals, unlikely to obtain refugee status, have been identified on numerous routes, while over 80% of all Syrian nationals were identified on the Eastern Mediterranean route (see Figure 1). In turn, our event study results pooling all IBCs together show that the EU-Turkey Statement led to a decline in the relative number of IBCs on the Eastern Mediterranean route – and a significant increase on the Central Mediterranean route. Moreover, the 12-month period following the EU-Turkey Statement shows a significant drop in likely irregular migrants on the Eastern Mediterranean route and a massive increase on the Central Mediterranean route. In contrast, the policy did not significantly change the number of likely refugees on the Eastern Mediterranean route and deflected to a much lower extent non-Syrian likely refugees to the Central Mediterranean, and not significantly so the likely refugees when including those coming from Syria. The evidence thus suggests that likely irregular migrants were more likely to change their trajectories, while Syrian likely refugees continued to cross the Eastern Mediterranean route.

FIGURE 1 Concentration of IBCs by Country of Origin and Average Asylum Acceptance Rates (2009-2020)

Source of figure 1: Mesnard, Alice, Filip Savatic, Jean-Noël Senne, and Hélène Thiollet. 2024. “Revolving Doors: How externalization policies block refugees and deflect other migrants across migration routes.” Population and Development Review, forthcoming.

Finally, we examine the differential effect of the EU-Turkey Statement by splitting the sample by proximity of countries of origin to the closest nearby route. On the Eastern Mediterranean route, the decline in IBCs from “far” countries of origin is greater than for “close” countries of origin. On the Central Mediterranean route, the aggregate number of IBCs from “far” countries rises more than from “close” countries. These changes are driven primarily by likely irregular migrants. These results were in line with our expectations as we anticipated that IBCs from a country located far from Turkey have lower changes in their relative migration costs when the route is blocked, and they change their trajectory.

Altogether, our results indicate a greater ability of likely irregular migrants to adjust to rising travel costs imposed by the EU-Turkey Statement. In contrast, likely refugees are more likely to be blocked from seeking asylum in Europe. The policy significantly impacts likely irregular migrants’ routes but has a limited effect on the migratory trajectories of likely refugees. These findings are in line with our expectations regarding the relative willingness and ability of individuals to adopt their migrations given the primary motive driving their movement. In addition, it reveals the failure of the EU-Turkey Statement as a policy on its own terms: it neither stopped irregular migration nor disincentivized the continued crossing of Syrians from Turkey as was explicitly intended.

Conclusion

Altogether, our study reveals that externalization policies such as the EU-Turkey Statement may have heterogeneous effects on individuals crossing borders without prior authorization. Those likely to obtain refugee status are less likely to adjust their trajectories following new policies in contrast to those likely not to be recognized as refugees. While externalization policies aim to stop “irregular” migration flows, they are more effective at deflecting likely irregular migrants to alternative migratory routes, while failing to protect refugees. Our study thus demonstrates both potentially unintended consequences of externalization policies as well as the inconsistency between policies deployed by EU states domestically and across their borders.

Effective migration policy design requires balancing control measures with humanitarian commitments. Consequently, border policies and externalization policies that aim to stop border crossings without considering the mixed nature of migration flows may abnegate legal and moral responsibilities to ensure humanitarian protection. Our research underscores the importance of evidence-based analyses of externalization policies and their impacts, advocating for a more nuanced and legally consistent approach to managing migration flows.

Acknowledgements/Funding

This research draws upon Savatic, Filip, Hélène Thiollet, Alice Mesnard, Jean-Noël Senne, et Thibaut Jaulin. 2024. “Borders Start With Numbers: How Migration Data Create ‘Fake Illegals.’” International Migration Review, Online First View, and Mesnard, Alice, Filip Savatic, Jean-Noël Senne, and Hélène Thiollet. 2024. “Revolving Doors: How externalization policies block refugees and deflect other migrants across migration routes.” Population and Development Review, forthcoming. The research presented in this article was supported by the European Union Horizon 2020 Grant No. 822806 as part of the Migration Governance and Asylum Crises (MAGYC) Project.

Footnotes

[1] Czaika, Mathias, and Hein de Haas. 2013. “The Effectiveness of Immigration Policies.” Population and Development Review 39(3): 487‑508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00613.x; Helbling, Marc, et David Leblang. 2019. “Controlling Immigration? How Regulations Affect Migration Flows.” European Journal of Political Research 58(1): 248‑269. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12279.

[2] Czaika, Mathias, and Hein de Haas. 2013. “The Effectiveness of Immigration Policies.” Population and Development Review 39(3): 487‑508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00613.x.

[3] Boswell, Christina. 2008. “Evasion, Reinterpretation and Decoupling: European Commission Responses to the ‘External Dimension’ of Immigration and Asylum.” West European Politics 31(3): 491‑512. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380801939784; Guiraudon, Virginie. 2003. “The Constitution of a European Immigration Policy Domain: A Political Sociology Approach.” Journal of European Public Policy 10(2): 263‑282. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176032000059035.

[4] There is no widely accepted definition of externalization. For a further discussion on how externalization has been defined, see Savatic et al. (2024) and Mesnard et al. (2024).

[5] Adamson, Fiona B., and Gerasimos Tsourapas. 2019. “Migration diplomacy in world politics.” International Studies Perspectives 20(2): 113–128. https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/eky015.

[6] Van Hear, Nicholas. 2011. “Mixed Migration: Policy Challenges.” Policy Primar. The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford. Accessible at: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/PolicyPrimer-Mixed_Migration.pdf.

[7] Frelick, Bill, Ian M. Kysel, and Jennifer Podkul. 2016. “The impact of externalization of migration controls on the rights of asylum seekers and other migrants.” Journal on Migration and Human Security 4(4): 190–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/233150241600400402; Jones, Chris, Romain Lanneau, and Yasha Maccanico. 2022. Access Denied: Secrecy and the Externalisation of EU Migration Control. Statewatch. Accessible at: https://www.statewatch.org/media/3781/secrecy-and-externalisation-of-migration-control.pdf; Oliveira Martins, Bruno, and Michael Strange. 2019. “Rethinking EU external migration policy: Contestation and critique.” Global affairs 5(3): 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2019.1641128.

[8] Arar, Rawan. 2017. “The New Grand Compromise: How Syrian Refugees Changed the Stakes in the Global Refugee Assistance Regime.” Middle East Law and Governance 9(3): 298‑312. https://doi.org/10.1163/18763375-00903007; Chimni, B. S. 2003. “Aid, Relief, and Containment: The First Asylum Country and Beyond.” In The Migration-Development Nexus, edited by Ninna Nyberg Sørensen and Nicholas Van Hear. International Organization for Migration (IOM), 51‑70.

[9] Kallius, Anastiina, Daniel Monterescu, and Prem Kumar Rajaram. 2016. “Immobilizing mobility: Border ethnography, illiberal democracy, and the politics of the “refugee crisis” in Hungary.” American Ethnologist 43(1): 25‑37. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12260.

[10] FitzGerald, David Scott. 2020. “Remote Control of Migration: Theorizing Territoriality, Shared Coercion, and Deterrence.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46(1): 4‑22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1680115.

[11] Thiollet, Hélène, Ferruccio Pastore, and Camille Schmoll. 2024. “Does the forced/voluntary dichotomy really influence migration governance?” In The Handbook of Human Mobility and Migration, edited by Ettore Recchi and Mirna Safi. Edward Elgar Publishing, 221‑241. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839105784.00021.

[12] Mesnard, Alice, Filip Savatic, Jean-Noël Senne, and Hélène Thiollet. 2024. “Revolving Doors: How externalization policies block refugees and deflect other migrants across migration routes.” Population and Development Review, forthcoming.

[13] Although we do not evaluate the relative validity of these reasons, we anticipate that refugees are less likely to be deflected – and more likely to be blocked by a policy – not matter what the underlying mechanisms at work.

[14] Carrera, Sergio, Leonhard den Hertog, Marion Panizzon, and Theodora Kostakopoulou, (eds). 2019. EU external migration policies in an era of global mobilities: Intersecting policy universes. Immigration and asylum law and policy in Europe. Volume 44. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff.

[15] Adepoju, Aderanti, Femke Van Noorloos, and Annelies Zoomers. 2010. ‘Europe’s migration agreements with migrant-sending countries in the Global South: A critical review.” International Migration 48(3): 42–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00529.x; Andersson, Ruben. 2016. “Europe’s failed ‘fight’ against irregular migration: Ethnographic notes on a counterproductive industry.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42(7): 1055–1075. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.113944; Cassarino, Jean-Pierre. 2014. “A reappraisal of the EU’s expanding readmission system.” The International Spectator 49(4): 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2014.954184; Gazzotti, Lorena. 2022. “Terrain of contestation: Complicating the role of aid in border diplomacy between Europe and Morocco.” International Political Sociology 16(4): 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olac021; Laube, Lena. 2019. “The relational dimension of externalizing border control: Selective visa policies in migration and border diplomacy.” Comparative Migration Studies 7(29): 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0130-x; Norman, Kelsey P. 2020. “Migration diplomacy and policy liberalization in Morocco and Turkey.” International Migration Review 54(4): 1158–1183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918319895271; Ostrand, Nicole, and Paul Statham. 2021. ‘Street-level’ agents operating beyond ‘remote control’: How overseas liaison officers and foreign state officials shape UK extraterritorial migration management.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47(1): 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.178272.

[16] An exception is one piece of ongoing unpublished research by Fasani and Frattini (2021).

[17] Savatic, Filip, Hélène Thiollet, Alice Mesnard, Jean-Noël Senne, et Thibaut Jaulin. 2024. “Borders Start With Numbers: How Migration Data Create ‘Fake Illegals.’” International Migration Review, Online First View. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183231222169.

[18] In 2022, the dataset was re-labeled from “irregular” to “illegal.” More details regarding this data are provided below.

[19] Czaika, Mathias and Constantin Reinprecht. 2022. “Chapter 3 – Migration Drivers: Why Do People Migrate?” In Introduction to Migration Studies: An Interactive Guide to the Literatures on Migration and Diversity edited by Peter Scholten. Springer, 49-71.

[20] de Haas, Hein. 2021. “A Theory of Migration: The Aspirations-Capabilities Framework.” Comparative Migration Studies 9(8): 1-35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4

[21] Frontex. 2023. “Monitoring and risk analysis: Detections of illegal border-crossings statistics download (updated monthly).” Accessible at: https://www.frontex.europa.eu/what-we-do/monitoring-and-risk-analysis/migratory-map/.

[22] Eurostat. 2023. “First instance decisions on applications by citizenship, age and sex – annual aggregated data (rounded) [migrasydcfsta].” Accessible at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/migr_asydcfsta/default/table?lang=en.

[23] For simplicity, we will just say EU moving forward.

[24] For details, see Mesnard, Alice, Filip Savatic, Jean-Noël Senne, and Hélène Thiollet. 2024. “Revolving Doors: How externalization policies block refugees and deflect other migrants across migration routes.” Population and Development Review, forthcoming. The primary routes are the Eastern Mediterranean route representing crossings form Turkey into Greece, the Central Mediterranean route representing crossing from Libya and Tunisia into Malta and Italy, and the Western Balkans route representing crossings across the Western Balkan states into Croatia and Hungary.

[25] The data distinguishes between “Geneva Convention Status,” “Humanitarian status,” “Subsidiary protection status,” and “Temporary protection status.”

[26] Savatic, Filip, Hélène Thiollet, Alice Mesnard, Jean-Noël Senne, et Thibaut Jaulin. 2024. “Borders Start With Numbers: How Migration Data Create ‘Fake Illegals.’” International Migration Review, Online First View. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183231222169.

[27] For details, see Savatic, Filip, Hélène Thiollet, Alice Mesnard, Jean-Noël Senne, et Thibaut Jaulin. 2024. “Borders Start With Numbers: How Migration Data Create ‘Fake Illegals.’” International Migration Review, Online First View. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183231222169.

[28] Eurostat. 2023. “First instance decisions on applications by citizenship, age and sex – annual aggregated data (rounded) [migrasydcfsta].” Accessible at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/migr_asydcfsta/default/table?lang=en.

[29] This represents the likelihood that individuals are likely to obtain refugee status and is based on public policies that have been adopted or are under consideration at the EU or member state levels. Our results are robust to the alternative threshold of 60.6%, which corresponds to the third quartile of asylum acceptance rates over the period 2009-2020.

[30] We restrict our analyses to four main routes (Eastern, Central, and Western Mediterranean and Western Balkans) and to the top 25 nationalities identified as IBCs, representing 94.5% and 96.1% of all IBCs, respectively.